To speak out about slavery in Mauritania is to risk losing your liberty (independent.co.uk)

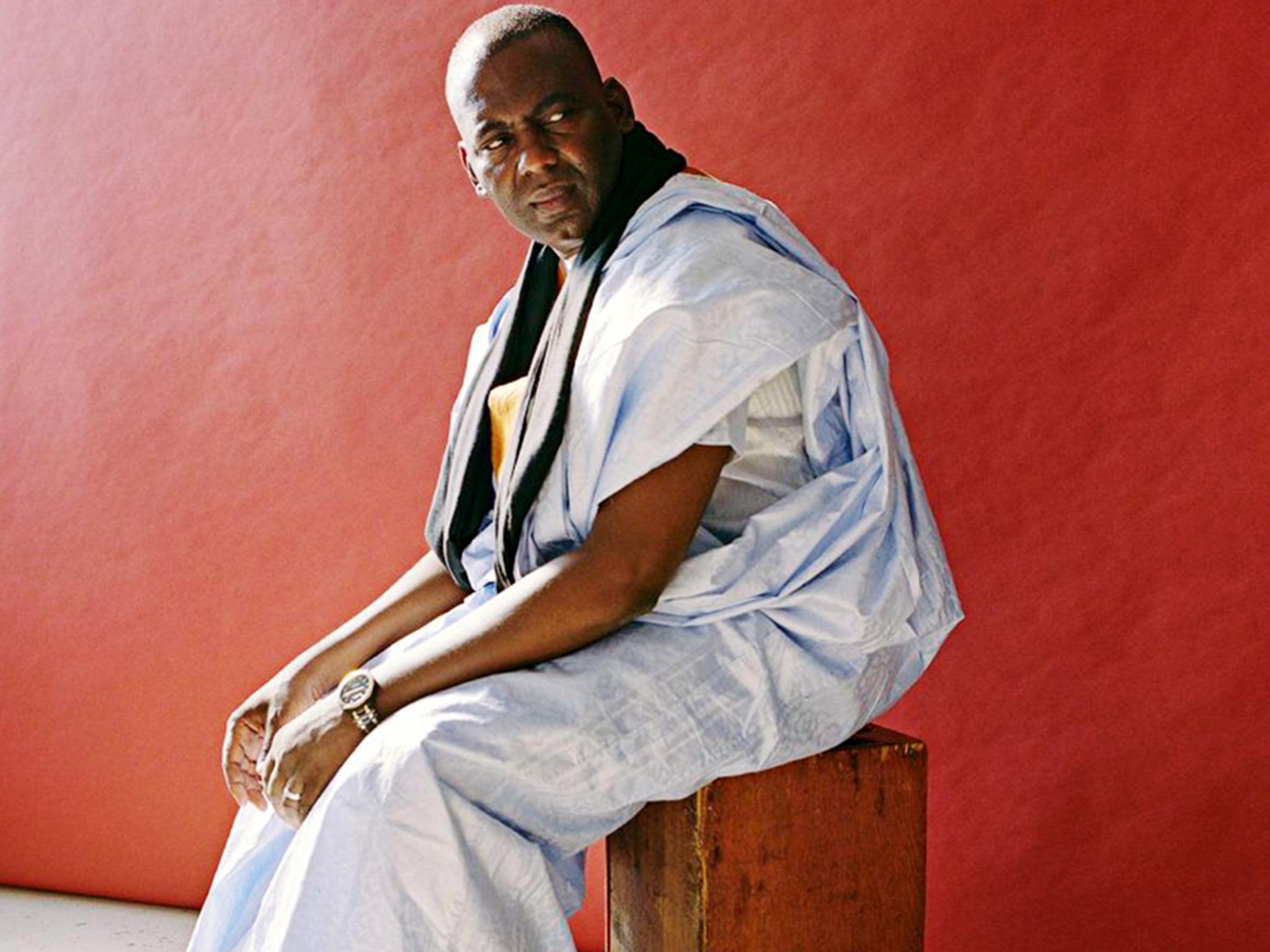

When Biram Dah Abeid announced his intention to run for political office on an anti-slavery ticket, he soon found himself in a dirty prison cell

Biram Dah Abeid was woken with a shock at 5.30am by police, who took him to a squalid, windowless prison cell at the station. But he wasn’t surprised. The day of his arrest last month was also the electoral commission’s deadline for candidates to register in the national elections, held on 1 September.

There is no political advantage to taking on the mantle of anti-slavery activism in Mauritania. Abeid, president of the Initiative for the Resurgence of the Abolitionist Movement (IRA), can confirm that, to his cost. Since announcing his intention to run for political office to take his anti-slavery agenda to the top, Abeid and his colleagues have endured ongoing persecution.

Just last month the anti-slavery community was celebrating the release of two activists and IRA board members, Moussa Bilal Biram and Abdellahi Matalla Saleck, from a remote Saharan prison where they had been held for two years.

The celebrations were short lived. It’s a familiar cycle.

Their arrest, in June 2016, came a month after Abeid himself was released from his last stint in prison in May 2016. A broad coalition of individuals and organisations came together to expose the injustice of his detention. Over 370,000 signed a petition hosted on Freedom United and calls were made around the world seeking his release. Eventually the supreme court ruled in favour of his second appeal and reduced the original charge to a minor offence that carried a maximum jail term of one year, which he had served almost twice over.

Since Abeid’s release in 2016, or rather during his two years of freedom, he’s added a couple more awards to his collection for his anti-slavery activism, including being made a Trafficking in Persons Hero by the US State Department. While in Washington DC, receiving the award, the Mauritanian authorities rounded up several of his IRA colleagues with accusations of taking part in an organised protest and charged them with incitement of riots and violent rebellion against the government.

Slowly the activists were released until just two, Moussa Bilal Biram and Abdellahi Matalla Saleck, remained in prison. The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention concluded that the detention of these activists was in violation of international law.

Despite his high profile, there is no reason to believe Abeid will fare any better in his treatment. It took a call from the chair of the Mauritanian Bar Association to get Abeid a small mat and a mosquito net in the dilapidated, dirty prison cell. On 13 August he was moved to Nouakchott’s central prison on remand for charges of attempted assault and the threat of the use of violence. Abeid disputes the claims, which critics have argued are trumped up.

Abeid had only been back in the country a matter of days, having returned from the US where he had participated in a Congressional Briefing on the issue of slavery in the Sahel. And Abeid knows his subject well. A son of a slave, he is a Haratin, a minority group that faces discrimination to such an extent that half the country’s Haratin population live as slaves with descendants “inherited” by their owners.

The shake-up Abeid represents in attempting to secure political office appears too much for the authorities to handle. Under the Sawab-IRA coalition, he intended to run in the national elections and had held public meetings in the country’s capital, increasing his share of popular support. The government has been under increasing pressure to address what is one of the world’s last chattel systems, passing a new law in 2015 and establishing a special slavery court. However, the picture overall is disappointing. Few cases have been heard, only a couple of prosecutions have been successful and the overriding message is that fighting slavery will land you on the wrong side of the law.

Abeid is clearly not easily silenced. However, taking on this system of slavery in Mauritania requires a level of bravery that is outstanding to those of us living in countries where political leadership is falling over itself to be seen as driving the anti-slavery agenda. Once again his case requires international attention, which will, in all likelihood, expose that charges brought against him are unfounded, inevitably leading to his release. However, if by holding Abeid until after the elections, the incumbent government quietens down voices of dissent and further beds in its iron grip, it will hail its actions a success.

Joanna Ewart-James is executive director of Freedom United, which has established a petition calling for Biram Dah Abeid to be freed